The description of the Battle at Perambani (better known as Pollilur), as Jacob Haafner calls the location of the battle between Tippoo Sultan of Mysore and the English forces under Luitenant Colonel Baily (Colonel William Baille according to historical sources) 10 September 1780. Haafner recounts of an accidental meeting with a combatant on the Mysorian side at a rest house. As part of his “Travels in a Palenquin” published in Amsterdam in 1808. It describes the early use of rocket technology by the Indian forces.

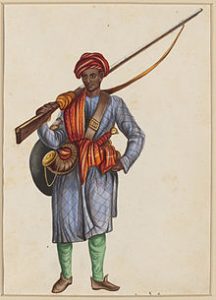

The Sepoy

The tough march had exhausted my travel companion Huau; he went to sleep immediately after dinner. I wanted to follow him in this – but the fierce thunder, the splashing of the rain, the noise of so many people together – made it impossible for me. I sat up again, lit a cigar; and under the hope of finding someone, with whom I could enter into conversation, to spend the time, I noticed not far from me, a Moor or Mohammedan – who was sitting all alone, chewing his betel.

I beckoned to him, and poured him a glass of arrack (*); after I had first rinsed it with the liquor. He took it politely, though with the left hand, at the same time requesting me also to excuse him, because of this impoliteness (†), in that he lacked his right – he had lost it as Sepoy, in the battle of Perambani.

(*) Most of the Mohammedans, would suffer death rather than to drink wine; because Mahomed has banned it according to the Koran strictly; but because he didn’t speak in his prohibition of any arrack or other strong liquors, they think that they are free, to use this without shyness, and with pleasure, without fear or guilt to themselves, or to violate the laws of the Prophet.

(†) It is considered by the Indians to be a great impoliteness, to give or receive anything with the left hand. They will not even touch their own food with that hand, because they use them for all sorts of impure pursuits.

I was delighted to meet someone who had attended this event personally and invited my Moorish friend to sit himself down on the mat with me, and to tell me of the details of this, for the English so fateful, battle, which he immediately was willing to do. His story of this battle, being completely consistent with what was known to me from other credible sources, I dare to offer the reader as genuine, with some needful explanations and additions.

Ambush.

It was at the very beginning of the war between the English and the Nabab of Massour, Hyder Alichan Bahader, in 1780; the Lieutenant Colonel Baily, with 800 Europeans infantry, 10 battalions Sepoys, some gunners, and 15 guns, returning from the province Guntoer (which he had been plundering), to unite with the great army, under the Major General Sir Hector Munro (who was camped not far from Chengleput,).

The bad Monsoon had just deployed itself; some rivers, which he had to cross were already very swollen, which obstructed and delayed his march somewhat, but by the enemy he was not troubled, except by some wandering rider bands, which occasionally made a point of wanting to attack in his rear. But, as it turned out afterwards, had only been intended to watch him, and inform Tippoo Saheb (*) of all his movements; who had placed a strong detachment of elite troops between him and Munro – and awaited him.

(*) Son of Hyder Alichan. In the continuation of this work, I will speak at length of the life, the deeds and the fatal end of the unfortunate Tippoo Saheb.

As soon as Baily received the explicit news of this, he stopped, judging himself to be too weak, to face the enemy.

Immediately he sent several Harkarrahs (* messenger, also spy) to General Munro, notifying him of the enemy’s intention and of his precarious and perilous state and requesting him to make a forward a motion with the great army, thereby favoring his union with him – and make the enemy pull back.

But Munro continued (the reasons for which I am unaware) motionless in his camp, without the least worry, it seemed, for Baily. Only three days later, he sent the Colonel Fletcher to him to help, with a company Cadets, two regiments Mountain Scots, and twenty companies grenadier Sepoys.

This detachment arrived, after having taken a wide detour, successfully to Baily; who, now believing to be strong enough to confront Tippoo Saheb, as soon as he might attack him, once again went on his way, without perceiving anything of the enemy (except a few light troops riders/cavalry, vaulting in the distance, who steadily stayed with him). Not even there where he expected it, in strength, to challenge him the way.

The second day of their march, the troops arrived, about twelve hours in the afternoon, very tired in a great woodland, called Perambani, which they had to cross necessarily, and in which they wanted to rest themselves a bit. – Here Tippoo Saheb had laid an ambush – which went to his desire.

Baily with his people, without the slightest suspicion of that, entered carefree into this wood. Scarcely they found themselves in its center, or they were greeted by three masked batteries, in front and at the flanks, which furiously began to play on them.

The Europeans quickly stormed one of these batteries and took hold of it, but the firing of the other two was so intense – that they found themselves compelled, to leave it again in a hurry, and return to the majority of their people.

Rockets

Rockets

More or less they saw themselves surrounded on all sides by the enemy; nothing was left to them other than to fight manfully – and, as much as it would be possible, to cut themselves a way through. They succeeded, not without many difficulties and opposition, to get out of the wood, where, because of the thickly growing trees, they could not deploy their troops; but here they found the camp of Massourers (Mysores), arrayed in battle order, before them, and new batteries, which thundered away on them.

Baily not shocked by this decides instantly. At his command the rumbling drums call to the battalion Quarré! the ranks divide themselves, flow together, and develop artfully again – and from the vast rows quickly forms a menacing square, defended at the corners with heavy artillery, as to where the enemy might attack, to be able to resist it, and to turn them back forcefully.

Now the Massour [Mysore] riders storm from all sides, on the movable fortress, encouraging each other with wild shouting – three times they attack – are three times they are forced to turn back with great loss. From a thousand guns, death persistently rattles to meet them. Like a quick flowing stream, interrupted in the fiercest of its course, by a broad and lofty cliff, which rises from the middle of its bed, – roaring foaming back – thus again and again they recoil.

Meanwhile the artillery of the English thundered away incessantly on the Massours gangs who conceded herein nothing to them, but still moreover, send them countless Fougeitos (*).

(*) The Indians make use in the war of a kind of fire arrows [rockets], which are called Fougeitos. It is an iron rod of eight to ten feet long, and about three inches thick; at one end thereof it has a heavy iron container tube filled with gunpowder, which, through a small hole, which is at the back of the container tube, being lit, the snake flies forth, with a prodigious speed, and steadily rotating, and can sometimes kill five or six people, or seriously hurt them. These rockets are dealt with by special people, and it takes a lot of power and art, to manage them, and to give them a horizontal direction.

Like thunderbolts they whizz murderously into their dense rows, but they, not paying attention to the fallen immediately close the ranks, immovable they stand, man to man, as an impenetrable wall – a formidable stronghold of threatening artillery, with daggers raised.

The Battle Turns

Thus was battled. Fear and hope, floated in turn, from one host to the other – all the attacks of the cavalry were beaten back – all attempts by Baily, to cut himself through the enemy, are in vain – when suddenly a rocket landing in the center of the square shatters a cart with gunpowder, and has it explode, together with three others. This dreadful accident brings confusion among Baily’s troops; dismay and terror seize the souls of his warriors; most, unaware of the cause of this terrible outburst, believing that the enemy is already raging in their midst; many of them step away from their position, and anxiously look around for escape – and in the undulating ranks wide openings appear.

This saw the son of the Massourian hero; perched high on the back of his mighty elephant he saw the decisive moment of victory – with thundering voice he cried to the general attack.

As fast as the Avoutrou (Mountain Eagle) pierces the air on his outspread wings, his riders again pour forward from all sides, with felled spears and terrible shouting – the earth trembles under the hoofs of their roaring horses. Just as quick the leaders of the British troops search to restore their ranks again. Their hasty effort increases the confusion; with loud cries and fearful clamor, they run along the confused lines of their warriors, encouraging them to receive the approaching enemy with the raised daggers of their guns, and to turn them back.

Like a hurricane interrupted in its devastating speed by a thick forest, attempts to find a way through with redoubled howling and rage until it penetrates at last, and shoots over the fallen trees into the echoing valley – so terrible are the repeated shocks of Massourian riders, onto the formidable square – wildly cheering, they finally break through, tearing it from all sides. The infantry and other troops streamed after them with gruesome shouting; while the English, surrounded on all sides and affected, their heads spinning by conflicting orders, unsure whom to obey – were desperately running here and there. Their ranks almost dissolved, all order and discipline has an end.

Ten thousand blades now lighten at once in the raised fists of Massours. Spears without count lift up their glittering tips. Like waves of the sea, with their foaming backs – thus the glimmering swords rise and fall on the heads of the British. It is not a regular fight of organized rows; it is a shrill slaughter, a murderous bustle. The snorting of the horses, the tumult and the shouting of the combatants, the screams of rage, the groans of the wounded – and the howling of wild despair, resounds on all sides. Dust and sand, mixed with the choking exhalation of men and horses, and the vapor of the smoking blood, rises up and surrounds the combatant with a thick cloud.

Some among the English plunge desperately in the outstretched spears, others look anxiously for a way to escape the hounding sword, and to save themselves from the terrible throng; but many, namely the Scottish and Bengal troops, unite and use their arms to die not unavenged. Baily is at their head, he urges them to valor – the risk increases his courage.

Like a wild boar, in the dark forests of Lonka (* Lonka, this is the old name of the island of Ceylon), attacked by fierce dogs, and the sharp arrows of Vadahs († wild forest inhabitants of Ceylon), neither fears, nor seeks to evade them. Sparks jump from his eyes, his brushes rise up along his curved back, sharpening his tusks on the gnarled trunk of a tree, and, casting himself furiously among his pursuers – cutting down everything that come before him, and persistently fights – until he, covered with wounds, crashes down – thus Baily fought and defended himself with his Europeans still a long time, and made many a foe bite the dust.

The English Defeated

The English Defeated

But gradually their small troupe shrinks together; from all sides they are struck down, and almost the Massourers have no enemies left to fight any more; everything is destroyed, everything is slain! the battlefield is covered with dead and dying. Triple the corpses are piled on top of one another, horses stumble over them, deeply they tread into the foaming blood – their bellies are painted with the splashing blood of the slain.

Baily with some few, escaped death (* It was with great trouble that the French Gunners, who were in Tippoo’s detachment, saved him with some of his officers and soldiers), and became prisoners of war.

As far Munro is concerned, who was located about seven English miles from the place where this battle took place; as soon as he had heard from some escaped Sepoys of Baily’s fate or he withdrew with the greatest haste to Chenglepet, six-and-twenty English miles from there: leaving his luggage – even his guns in the run; which all fell into the hands of the enemy. The loss of the English is counted, in that battle, at about 2100 Europeans and 8000 Sepoys, which were all sabered down.

Thus ended this memorable battle; the first, which was fought between the two warring parties. It would have been finished with the English on the coast, had Hyder Aly then, with the bulk of his army, gone to Madras, while Tippoo meanwhile, with a reinforcement, had surrounded the troops of Munro in Chinglepet. Madras, in the state it was in then, would surely have fallen before it could have received help from Bengal – and what boon would it have been for the Indian people! What a blessing, what a glory for the Nabab – having driven the white tyrants from the coast, and having destroyed one of their strongest robber nests.